I will solve a stupid management problem using old mathematics and Google.

Imagine that you have N employees who work side by side in a row. For more conviviality you decide to arrange them in a different order every day, so that after some time each employee has worked besides each of the others at least once. How to do so in a minimal number of days ?

A little bit of context

This problem appeared a few weeks ago in the Reddit/Python forum, when someone posted this:

“I think it is good to shuffle the team around. (…) Here is the function that we use to randomize our team making sure that you do not sit next to someone you are already sitting next to [supposing that all are sitting in a row].”.

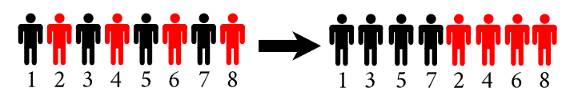

Stated like this, it is a very simple problem which doesn’t require a complicated algorithm, you just shuffle the order of the previous day as follows, and it will do the trick:

This shuffle can be written in one line of Python:

1 2 | |

The problem with this shuffling, as someone on Reddit pointed out, is that even if you shuffle a great number of times there is no warranty that everyone will have worked besides everyone else in the end. For instance in the shuffling shown above employees 1 and 8 will never be neighbours. And it seems that you can imagine a shuffling as complicated as you want, there will always be a number of people for which it will fail to create all possible pairs of neighbours !

This leads us to our problem: how to ensure that all possible pairs of neighbours will be created, and in a minimum amount of time ? We will see that there is an optimal strategy. It does NOT use a shuffling, but rather a 120 years old mathematical construction.

First elements of solution

If you have N employees, then they can form N(N-1)/2 pairs. Each day you create at most (N-1) new pairs of neighbours by placing the employees on a line. Therefore you will need at least N/2 days to create all possible pairs. This means that you cannot solve the problem in less than N/2 days if N is even, and (N+1)/2 days if n is odd. What we will show is that it is actually possible to solve the problem in N/2 days (for even N) or (N+1)/2 days (for odd N).

In fact we only need to solve the problem for even N, and the solutions for odd N will follow very simply. To see this, suppose that you have an odd number N of employees. If you add one imaginary employee, you come to an even number (N+1) of employees. Suppose that you have found a solution for these (N+1) employees, which means that you have found a series of (N+1)/2 arrangements which form all pairs of neighbours. Then remove the imaginary employee from each of these arrangements. What you obtain is a series of (N+1)/2 arrangements, in which all pairs of the employees 1 to N are formed. In other words, you have solved the problem for N.

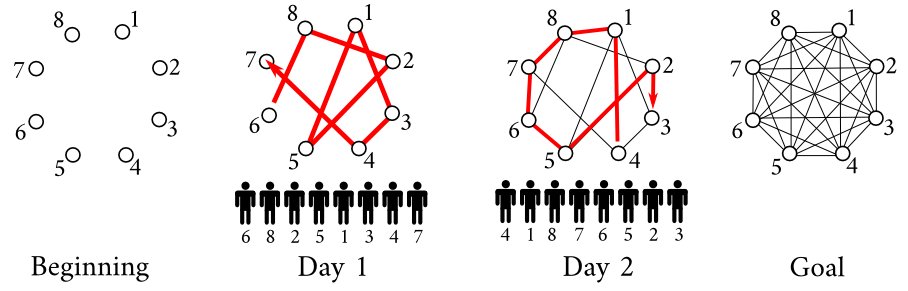

Representing the problem with a graph

This problem can be very well represented using a graph whose nodes are the employees. Each day we add an edge in the graph between each pair of employees which have been neighbours, our goal being to cover all the possible edges of the graph:

Notice how each day you actually trace a path in the graph.

Now our problem has become: given a graph of size N (even), find N/2 paths, each going through each node exactly once, such that they cover all the possible edges of the graph.

And here is a sketch of a solution that will always work:

The first path is a simple pattern 1, N, 2, N-1, etc. and the others are just rotations of the first path. The nice thing with the graph representation is that I can use a simple geometric argument to prove that these paths will cover all the edges: if we place the N nodes of the graph cyclically like in the figures above, the path number K will have edges that make an angle $2K\pi/N$ or $(2K+1)\pi/N$ with the horizontal line. So the different paths have edges of completely different angles. For this reason an edge cannot belong to more than one path. Since there are N/2 paths and each path covers N-1 different edges, the paths cover N(N-1)/2 edges in total, which is all the edges.

This construction of paths may seem simple to some of you, but I couldn’t figure it out on my own, and it is an application of a 19th century mathematical trick called the Walecki construction, which I found after some googling, as I explain in the last section.

Solution

If N is even, arrange the employees in this order the first day: 1, N, 2, (N-1), 3, (N-2), etc. From day 2 to day N/2, place the employees by taking their arrangement of the day before and replacing employee 1 by 2, 2 by 3, 3 by 4… and N by 1.

If N is odd, add an imaginary (N+1)th employee, solve the problem for the N+1 employees using the mehod above, then remove the imaginary employee from each of the arrangements obtained.

Here is the Python implementation of this solution:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 | |

>>> place(12)

[[1, 12, 2, 11, 3, 10, 4, 9, 5, 8, 6, 7],

[2, 1, 3, 12, 4, 11, 5, 10, 6, 9, 7, 8],

[3, 2, 4, 1, 5, 12, 6, 11, 7, 10, 8, 9],

[4, 3, 5, 2, 6, 1, 7, 12, 8, 11, 9, 10],

[5, 4, 6, 3, 7, 2, 8, 1, 9, 12, 10, 11],

[6, 5, 7, 4, 8, 3, 9, 2, 10, 1, 11, 12]]

[Bonus] How to be a graph theorist with Google

For the anecdote, I was not really happy when I figured out that the problem could be represented with graphs, as I really know nothing about graphs theory.

However, I thought that, as we are dealing with graphs in which everyone is connected with everyone, they must have some interesting properties. So I googled fully connected graphs, which led me to Wolfram Mathworld’s article on Complete graphs (apparently that’s their real name), where we can read on the 6th line:

“In the 1890s, Walecki showed that complete graphs Kn admit a Hamilton decomposition for odd n, and decompositions into Hamiltonian cycles plus a perfect matching for even n (Lucas 1892, Bryant 2007, Alspach 2008). Alspach et al. (1990) give a construction for Hamilton decompositions of all Kn.”

That’s not what you’d call crystal clear, but it says decomposition several times, and that sounds like what I want to do. So I looked for the last reference, Alspach 1990. Springer, the publisher, gracefully gives you access to the first two pages for free. The good news is, they contain all the properties and proofs that we need, in a compacted yet very understandable form. Let us see in details what they say.

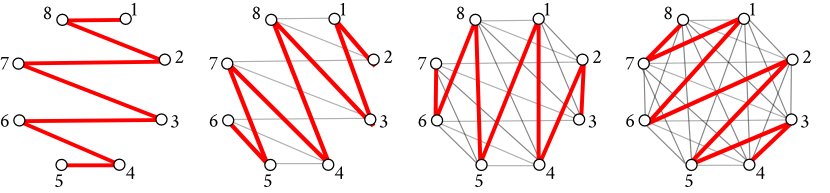

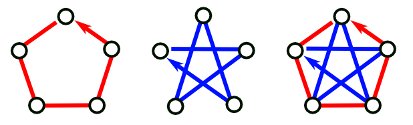

It starts with Hamiltonian cycles. An Hamiltonian cycle is a path that starts from one node, visits every other node exactly once, and come back to initial node. The two first figures below are two Hamiltonian cycles for a graph with five nodes:

As you can see, these paths have no edge in common, but put together they cover all the edges of the complete graph. They form what is called a Hamilton decomposition of the complete graph.

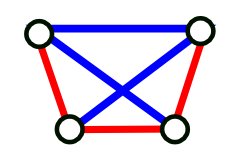

Now what happens if you remove one person from the graph, say, the person at the top ? You get this:

You obtain two paths that describe a solution of our problem for N=4 employees ! And it will always work: if you can find an Hamilton decomposition of the complete graph of N+1 nodes (N being even), just removing one node will give you a decomposition into paths of the complete graph of N nodes, from which you can deduce a solution to our problem with N employees.

So now the important question is: how do we find an Hamiltonian decomposition of the complete graph of (N+1) nodes (N+1 being odd) ?

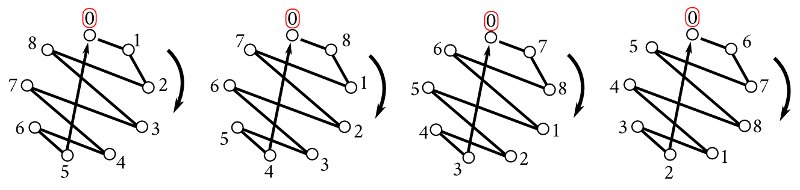

This has been answered in 1890 by Walecki with the following construction. I use the same notations as in Alspach 1990. Note that node 0 stays in place while all the other numbers rotate clockwise from one cycle to another.

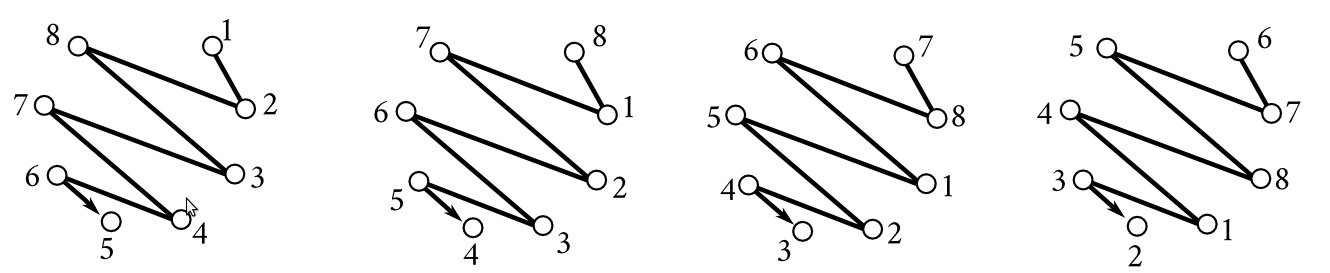

There is no extensive proof in Alspach 1990 of why this covers all edges, but I guess that a geometrical proof, like the one I give in a previous section, could do the trick. Now all we have to do is to remove one node of the graph: we choose the node 0:

With just a few tweaks in the order of the nodes, we come to the solution presented in the previous section.